A Quick Guide to Airline Network Ramp-Up

Restoring Airline Networks Under Immense Uncertainty

For established carriers, building their network is a continuous task they deal with every single day. Thus, accommodating growth usually means incremental changes to the network – a new destination, a larger aircraft type, or additional frequencies on high-volume routes. In some cases, however, changes can be more than incremental – for example, if an airline embarks on a strategic expansion path. The currently ongoing network relaunch of airlines is a suchlike expansion, but on steroids. It must be kept in mind that most airlines worldwide come back from a complete lock-down with no operations at all – or a status close to that. With a baseline close to zero, every growth trajectory is steep, and far from incremental. At first glance, this challenge may still look manageable, since what is this ramp-up other than a return to the previous state? Although this statement is basically true, there are three triggers that make rebuilding the network an intimidating task:

- Re-starting the network (almost) from scratch implies that all resources must be brought back from a kind of hibernating mode – aircraft from extended grounding, crews from furlough, and all external providers from a forced break. Timing is of the essence, resulting in critical paths once the new schedule is published

- In contrast to incremental expansion, restoring the network occurs at much higher growth rates and speed. In a normal schedule period, an established carrier may add 2, 3 or even 5 % capacity if demand is strong. However, airlines now have to start almost from zero capacity, reactivating 20, 30, or even 50 % of their former flights within a few weeks or months. Together with the still immense uncertainty with respect to returning demand after the first wave of the global pandemic, this implies a daunting risk exposure for network managers

- For a limited capacity expansion such as an additional frequency on an existing route, or even a new route, the business case is usually clear from the beginning. During the current crisis, however, the massive capacity additions of the ongoing network re-launch skates on the very thin ice of an unprecedented situation – the commercial viability of a restored flight may turn out no earlier than it is in service.

Brian Pearce, chief economist of IATA, predicted in his report on 1st July 2020 a recovery of global traffic volume (in terms of RPK = Revenue Passenger Kilometer) to between 47 and 64 % by the end of the year, compared to the figures in December 2019. Due to the inherent uncertainty in this situation, the risk exposure is very high for every airline: being too slow with the capacity relaunch may make interested travelers cross over to the camp of competitors. And being too quick will cause significant cost without sufficient revenue coverage – a combination that may well turn out lethal after the painful lock-down. Thus, it is vital for airlines to find indicators for the returning demand – and at the same time deploy a network ramp-up concept that mitigates the risk exposure as much as possible.

Five Steps to Grow a Network

In a non-incremental growth scenario like the current one, every airline needs to achieve a balance between the capacity expansion on the one hand – creating additional operating costs – and the increased revenue potential on the other hand. While the additional cost of an expansion becomes effective as soon as the new capacity is in place, the expected revenue is uncertain. This is critical since demand is even more unforeseeable after a crisis than in a stable business environ-ment.Luckily, a capacity expansion can be achieved in different ways, which gives the carrier a certain leeway to mitigate the capacity ramp-up risk: contingent on the geographic location of the hub and on the fleet composition, an airline can choose between different route types, aircraft sizes, and service frequencies when it expands its network. As for the entire network, there is so single optimum solution for the expansion path; however, the following rules of thumb for a balanced expansion have been successfully executed by various hub and spoke carriers in the past, e.g. by Turkish Airlines during their strategic growth program over the past ten years:

- Start with routes to major continental destinations (trunk routes or markets with high-value connected traffic potential), including hubs of competitors

- (Re-)Launch long-haul flights to primary intercontinental destinations (long-haul trunk routes), including hubs of competitors

- Add secondary continental routes

- Extend long-haul network to secondary destinations (especially non-hub bases of competitors)

- Establish services to small continental routes (provided that a dominant or even monopolistic position can be achieved in that market)

The first two steps obviously aim at quickly achieving a good base load for the expanded or reactivated network at limited risk. Airlines from emerging regions such as Turkish Airlines or the Gulf carriers have diligently pursued this approach for their strategic growth plans. Turkish Airlines has been especially successful over the past decade by building a domestic, short-and mid-haul feeder network, upgrading their fleet and hub performance, and finally expanding their intercontinental network. Once a certain destination worked well and the demand grew, they added a second or third frequency per day to become the dominant carrier in that market.First, the short timeframe for a massive capacity relaunch is historically unprecedented, and second, all airlines must rebuild their networks, which makes the risk of being either too quick or too slow even more precarious.The third and fourth step can be perceived as a direct attack on the home carrier of a target country, trying to entice O&D traffic away from that carrier in his non-hub bases. This approach may well lead to a competitive battle since the attacked home carrier will quite likely strike back. However, in times of the pandemic crisis, an aggressive approach like this may be perceived as inappropriate by the aviation commu-nity.

However, reactivating a network from scratch after the COVID-19 crisis – within weeks or months – is by far more challenging than expanding an existing network in a normal business environment over many months.The fifth step – the addition of small but profitable niche markets – is obviously contingent on the recovery of demand on such routes after the crisis. However, this step is ‘icing on the cake’ rather than a core element of the ramp-up strategy.

Leverage the ‘S-Curve Effect’

If the first four or five steps listed above have been success-fully performed, and the recovery of demand seems to continue, there are two more steps to attract demand and accommodate it in an efficient way:

- Launch additional frequencies to destinations under points 1 to 4 above, potentially combined with a switch to slightly smaller aircraft types on routes to secondary destinations

- If the recovery continues: switch (back) from smaller to larger aircraft types to destinations under points 1 to 4 above, in order to benefit from decrease of unit cost and subsequent improvement of competitiveness

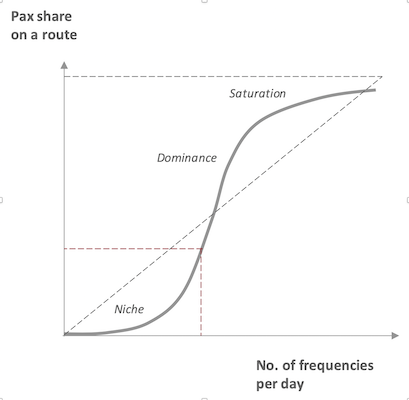

These two steps aim at finetuning the efficiency and profitability of the re-launched network by optimizing the trade-off between aircraft size and service frequency, which is a vital parameter of every network – within or outside a crisis. Operating larger aircraft improves the unit cost position, but reduces the number of feasible flights per day or week, resulting in a compromised competitive position if other airlines offer a higher frequency of services on the same route.The latter phenomenon is often referred to as ‘S-curve effect’, describing a situation where a dominant airline on a certain route is able to attract more additional passengers than it seems to ‘deserve’ with an additional frequency (e.g., 7 % more passengers with 5 % more seats), while a niche player could end up with less additional passengers than its capacity addition would suggest (e.g., 3 % more passengers with 5 % more seats). This effect is driven by the buying behavior of service-oriented passengers such as business travelers, who perceive the frequency pattern of the incumbent as fundamentally superior to that of smaller or even niche players. Thus, an incremental frequency of the former attracts more additional passengers (to the entire flight pattern!) than one of the latter.

Figure 1: Experienced-based S-curve effect for airline competition on single routes [Franke, lecture script “Strategic Network Management”, IUBH Bad Honnef, 2019]On the other hand, business travel demand may be weak for a longer time than leisure travel, so the S-curve effect could become relevant again not in the short run, but rather at a later stage.

Manage the Ramp-Up Risk

Ramping up a network imposes considerable risks already in ‘normal times’, because it costs a fortune and shows a mediocre resilience to intensive competition or external disruptions. This is, however, even more true during the current pandemic crisis, because the initial lock-down has been unprecedented, the relaunch of capacity must be performed much quicker than in the course of a strategic network expansion, and the return of demand is much more uncertain.This specific setting boosts the imminent risks. For example, it is intuitive to start the relaunch with short- and mid-haul flights (steps 1 and 3 as listed above), since they are significantly cheaper than long-haul flights. On the other hand, hub and spoke carriers generate a dominant share of their revenues and profits with intercontinental services, which are not only contingent on a recovery of the respective demand, but also on the termination of international travel bans. Thus, steps 2 and 4 may have to wait – a fact that does not only limit the revenue potential, but also the efficiency of hubs, since it prevents the delicate balance between short-haul feeder flights and long-haul flights from being restored.

Likewise, the leverage of the S-curve effect as described above may not work – at least not on many routes – under the conditions of a global crisis. Filling a first short- or mid-haul flight from a major non-hub destination is often easy, especially with an attractive service concept and discounted fares. However, to stay competitive and attract time-sensitive business travelers, a second or even third daily frequency needs to be added soon (step 6 in the above list), which requires more and more cross-subsidies from the long-haul flights.Either the additional flights push down the overall seat load factor, or the carrier dampens that effect with smaller aircraft types, but pays the price with a deterioration of the unit cost position. Furthermore, business travelers’ demand for air transport seems to recover more hesitantly than that of leisure travelers. During the current crisis, the respective routes may thus consume more cash than the few relaunched long-haul flights can contribute, leaving the respective carrier with an unsustainable position.Some carriers are in an even more challenging position, since their local catchment is small, and short-haul flights are only a minor part of their business. For example, Gulf carriers such as Emirates, Etihad, or Qatar operate only few short- or mid-haul routes, so they are forced to re-activate their cost-intensive long-haul operations right away despite the significant capacity risk. In contrast, low cost carriers focus on continental networks with narrow-body aircraft without cross-subsidization – for them, ramping up a network with individually profitable routes is by no means unprecedented, but rather business as usual. However, the massive capacity risk induced by the uncertain recovery of demand hits low cost carriers as well.

Conclusion and Recommendation

The pandemic crisis has forced airlines into an almost complete lock-down, from which they now need to recover. The return of demand for global air traffic is highly speculative, making the relaunch of expensive capacities a tremendously risky task especially for hub and spoke carriers. Being too cautious could drive loyal passengers into the arms of competitors, being too bold can easily lead into bankruptcy. In this disturbing situation, the following rules of thumb may provide at least some guidance:

- Acquire every piece of information on potentially returning demand you can get hold of to mitigate your capacity risk. Every cent spent for new indicator concepts or COVID-19-adjusted demand forecasting models will be well-invested – even more so since these advanced forecasting models will become a standard after the crisis

- If you are an executive or a network manager of a hub and spoke carrier, start thinking like a low cost carrier: forget for the time being sophisticated levers such as fare mix or cross-subsidization between more and less profitable routes – just go for routes that can be operated fully stand-alone. Furthermore, lean structures and low unit costs are always helpful to survive in a nervous market environment

- Pursue the five-plus-two-step-approach described above, or at least those steps relevant for your network. Keep in mind that the first two steps are mandatory to reactivate a network, but every airline will go for these trunk routes, so competition will be fierce. Steps two and four depend on the termination of international travel bans and quarantine enforcement, while three and four may lead to direct confrontation with local incumbents. Steps six and seven deal with further growth on existing routes, raising the need to deal with the trade-off between aircraft size and service frequency.

Industry experts as well as economists expect that the post-pandemic volume of air travel will be below the pre-crisis status – thus, the ongoing ramp-up of airline networks lacks a clear target for the restoration of traffic. Consequently, network managers need to continuously update their perspective on upcoming demand, and adjust their growth plans whenever appropriate.The suggested approach is still risky, but it bears the potential to establish a self-sustaining growth cycle in global air transport. Right now, travelers are not only reluctant to fly since they have lost their jobs or lack money – many clients are simply unsettled by travel bans and airline lock-downs. If carriers demonstrate confidence by restoring their flight programs, this will encourage potential travelers to regain their confidence to fly as well.